Summary of Education Sector Analysis

17. Summary of Education Sector Analysis

Education sector analysis conducted for the sector plan showed an education sector that, despite slow improvements, over the years continues to be broken at multiple places. An overwhelming number of children are not in schools. Many drop out of schools, while the remaining do not have adequate schooling opportunities. More girls are out of school than boys. All students, boys and girls, who have the opportunity to be in school learn way below par. The sector analysis identifies direct and indirect causes for the situation. It looks at the governance and management structures, processes and inputs to assess the reasons for the outcomes. However, it presents these findings with a limitation. The paucity of information, especially, in critical details due to either lack of data or research or both. That is why research and data (or lack of them) have been identified as important areas of reform to be specifically focused. The sector requires major changes in the approach to reform service delivery and to ensure equal opportunities to all children for a better future.

Challenges of the Context

17.1. Challenges of the Context

Low population density is the most overarching feature with a large shadow on all development work. Balochistan covers 44% of Pakistan and houses only 6% of its population. Secondly, the province is multiethnic with multiple languages with Balochs and Pashtuns being the largest ethnic groups. According to the 1998 census, 55% of the population identify themselves as ethnic-Baloch90. Pashtuns consist 30% of the population, followed by Sindhi speakers at 6% of the total population. Followed by the Punjabis (3%) and Urdu-speakers (1%), who are often collectively referred to as the “settlers”. The Hazaras are another minority ethnic group with a population of approximately 500,000.

Strong tribal affiliations established through centuries dominate social and political decisions and, often, overwhelm the formal governance structures91. Strong patriarchy dominates social interaction and the household. Resultantly, Balochistan has the weakest gender statistics among all the provinces. Political, economic and social authority is almost always reserved for men. Of all the provinces of Pakistan, Balochistan has the lowest percentage of women (10%) who participate in major household decisions, including decisions pertaining to health care, major household purchases, and visits to family or relatives.92 Similarly, Balochistan has the highest percentage of women who have experienced physical violence (49%) since the age of 15.

Other features of underdevelopment include high levels of poverty, poor health indicators, and low literacy rates. According to the multi-dimensional, Poverty Index 2016, Balochistan has the highest rate of multidimensional poverty among all provinces in Pakistan.93 Nearly three out of every four persons in the province are living in multi-dimensional poverty. Similarly, Balochistan also has the highest average intensity of deprivation (55%) among all provinces. This means that each poor person in the province, on average, is deprived in more than half of the indicators included in the index. Multi-dimensional poverty in rural areas of the province (85%) is significantly higher than in urban areas (38%). Quetta, Kalat, Khuzdar, Gwadar and Mastung, in that order, are the least poor districts whereas Chaghi, Ziarat, Barkhan, Harnai, and Killa Abdullah respectively are the poorest districts in the province. The pace of progress has been uneven within the province.

90 This figure also includes the Brahui-speakers of the province. Although Brahui is a different language and is believed to have different origin, Brahui-speakers identify themselves as a part of the larger Baloch ethnic group.

91 Haris Gazdar, Balochistan Economic Report: Background Paper on Social Structures and Migration (Karachi: Collective for Social Science Research, 2007), pp.14

92 PDHS 2017-18

93 Pakistan Multi-dimensional Poverty Index 2016

Balochistan has the lowest percentage of fully-immunised children, highest percentage of under-five children suffering from Diarrhoea and lowest rate of contraceptive use (16%) of all provinces. It has the highest Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR) and second-highest rate of under-five mortality and stunting.

Figure 17-1 shows the basic health indicators: fully immunised children, children under 5 suffering from diarrhoea, women that have received TT injections and doctor-assisted deliveries. Balochistan has the lowest figures in all except children suffering from diarrhoea.

Figure 17-1 Health Indicators

The province also has the highest maternal mortality rates at birth as well as highest infant mortality rates at 78 per 1000 live births.

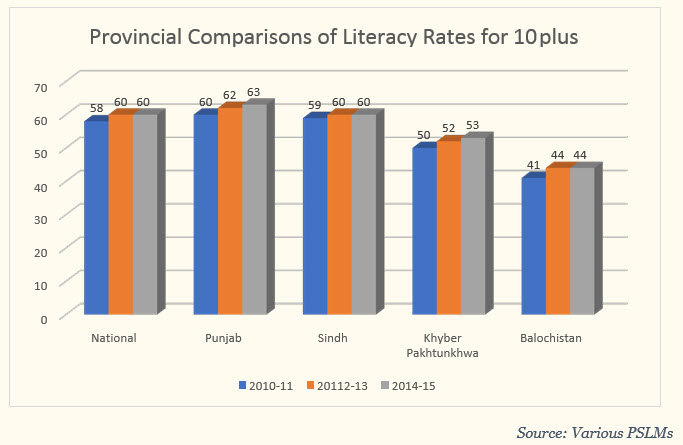

Similar to other indicators, Balochistan has the lowest literacy rates in the country. This holds true for both the 10 plus and 15 plus categories. In the 10 plus there is a slight improvement from 2010-11 to 2014-15, but still the values are about 9 percentage points lower than the next lowest of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and 16 percentage points lower than the national literacy rate as presented in Figure 17-2.

In the 15 plus category, the values go down for all jurisdictions but the gap between Balochistan and others increases. With Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, it enhances from 9 percentage points to 11 and from the national figure the gaps increases to 19 percentage points

Balochistan has remained a major destination for refugees coming from Afghanistan. According to the UNHCR, there are currently 324,280 registered Afghan refugees in the province.94. There is also an equally large number of unregistered Afghan refugees in Balochistan. The ethno-linguistic ties between refugees and certain ethnic groups of Balochistan, mainly Pashtuns and Hazaras, make Balochistan prime destination for Afghan refugees. Over the past decade, many refugees have returned back to their country. However, a significant number still remains in the province.

The province is exposed to a number of natural hazards, including droughts, floods, earthquakes, and dyke or dam failures; landslides and cyclones. In the past, these hazards have resulted in some major disasters, such as the Ziarat earthquake of 2008 and the floods of 2010. Historically, Balochistan has faced the highest disaster risk from droughts, earthquakes and floods. Recurring droughts are among the most significant challenges faced by the province, with serious implications for livelihood. The main reason for droughts in Balochistan is lack of rainfall over an extended period of time.

The Education Sector

17.2. The Education Sector

Overall poor performance of education is the result of inadequate performance in multiple areas. These include learning, access and participation, research and data and governance. TVET, the other sub-sector included, has even weaker results.

94 UNHCR Website 2019

Learning

17.2.1. Learning

Learning levels of school children are very low. Results and feedback from various sources confirm this situation. Children cannot read and have very low skills in numeracy. The problem persists even for learners who manage to survive school and go on to universities.

In 2013 Pakistan Reading Project (PRP) funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) conducted its baseline study. The results made two major revelations:

I. 42% children were zero readers in Urdu. This means they could not even recognise a single word. This reads starkly with the rest of the country where the percentage was 22%

II. Another 41% children read below the requisite standards

Table 16-1 below shows reading and numeracy skills for primary school children in grade 3 and 5.

Table 17-1 Reading and Numeracy Skills of Primary School Children

|

Reading and Numeracy Skills of Primary

School Children |

||||||

|

Region |

Class 3 |

Class 5 |

||||

|

|

Who can

Read

Sentence (Urdu/

Sindhi/ Pashto) |

Who can Read Word

(English) |

Who can do Subtraction |

Who can

Read

Story (Urdu/

Sindhi/ Pashto) |

Who can Read Sentence

(English) |

Who can do Division |

|

Balochistan (Rural) |

28.3 |

30 |

59.9 |

40.1 |

34.2 |

43.2 |

|

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Rural) |

54.6 |

57 |

80.4 |

57.9 |

54.9 |

69.3 |

|

Punjab (Rural) |

56.6 |

53.4 |

69.5 |

68.6 |

64.5 |

60 |

|

Sindh (Rural) |

32.3 |

36 |

44 |

42.7 |

25 |

31.8 |

|

Source: Annual

Status of Education Report 2018 |

||||||

For most of the skills tested, Balochistan and Sindh have the lowest numbers. In Urdu reading of a sentence (a very basic grade 1 SLO as per the curriculum) only 28.3% could read a sentence in Grade 3. By Grade 5 only 40% could read a story in Urdu. The situation in English remains worse, as in Grade 3 Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) tests for reading one word in English, and in Grade 5 reading a sentence (again a very basic SLO for Grade 1).

In addition to the above classroom observations carried out for the sector analysis show that children only rote memorise. Critical analytical ability is not developed. This is depicted even in the case of those who manage to successfully survive school and complete, a minimum of, graduate education. Reports of the Balochistan Public Service Commission (BPSC) and the Federal Public Service Commission (FPSC) speak of ‘declining standards of education’ and ‘cramming instead of in-depth analysis’ respectively.95.

The learning crises in the province has resulted from gaps in three areas:

I. The Learning Design

II. The Teaching Learning Process

III. Child Welfare

Learning Design

I. Learning Design The learning design includes curriculum framework, scheme of studies, curriculum and textbooks. The teaching-learning process includes teacher effectiveness and assessments and examinations. The latter having an overlap with the former and is, therefore, a sub-c0mponent of the teaching-learning process. And finally, child welfare; the most neglected component of the entire framework. Learning design (consisting of curriculum framework, scheme of studies and textbooks) has emerged as a major source of poor learning in the analysis. It is disconnected from the realities of the child and resultantly fails good and bad teacher equally. The process of curriculum development is not fed by any research on the needs of the child when he or she enters school as well as, the requirements of the exit point, which means expectations and requirements of the world after school. All components of the learning design have been developed on a set of assumptions about the learners that do not hold except for a minute minority of urban elite. The most glaring, and damaging, example is the language policy. Children are expected to learn to read English and Urdu early in grade 1, whereas an overwhelming majority of them (about 99%) do not have any knowledge of the languages as they enter schools. Textbooks follow a similar pattern. Resultantly, the teacher cannot connect with the child. The design fails good and bad teachers equally.

Teacher Effectiveness

II. Teacher Effectiveness

While learning design incompatible with the reality of the child is an important factor in the outcomes, teacher effectiveness remains low overall due to other factors also: effectiveness being a result of performance-driven by motivation, competence and resources and availability. The teacher is a member of an organisation and not an independent actor. Therefore, an organisational lens has been used for the analysis. The results conclude that teachers are largely ineffective. This is due to low motivation, as well as, weak ability and a paucity of resources. Motivation is impacted by a number of factors. Teachers are not treated as autonomous professionals but as part of a power-based official hierarchy. Non-inclusion in decision making or feedback, absence of an effective grievance redressal mechanisms, limited opportunities for self-actualisation including an unclear career path forms the core set of causes for low teachers’ motivation. Salaries have generally improved for teachers and are a multiple of the average in the private sector. However, in case of primary school teachers, the lower grade (which means lesser salaries), and treatment as the lowest in the hierarchical rung, further dents the morale.

Teacher competency also remains weak. Again this may partly be due to unrealistic expectations of the curriculum. Irrespective, studies on teacher’s competence, and classroom observations for the ESA, clearly show that the majority of teachers lack content knowledge and have poor pedagogy. Teaching is a one-way traffic with students not encouraged to ask questions. Presence of multi-grade situations in almost 72% primary schools (with 43% being single teacher schools) further pushes the teaching-learning processes towards rote

95 Public service commissions have the mandate to conduct examinations for selection of personnel in officer positions including the elite federal and provincial civil services.

memorisation. Finally, when it comes to resources and facilities, the teachers face a similar situation as the child.

Teacher competency itself is a product of the quality of pre-service teacher education, recruitment processes employed and professional development processes. There are gaps in all three. Pre-service teacher education continues to be the weakest link. There are three public sector universities and 17 colleges of elementary teaching that run pre-service teacher education programs. The latter under the direct administrative control of the Secondary Education Department through the Bureau of Curriculum and Extension Centre (BOC&EC). Bulk of students study in these colleges. Faculty appointed in these colleges have inadequate qualifications and capability to run graduate programs. These were required to be upgraded as per the recommendations of the last ESP through a faculty development program. Such a program never got off the ground. For recruitment, the processes have become more merit-based in recent years but some confusion continues on qualifications; as individuals with the older, lower quality, certification can also apply for teaching posts. The entire teacher recruitment process requires a reassessment from, both, quality and quantity need perspective.

It will, at least in the long run, resolve the most immediate and serious concern of teacher availability in the majority of districts, especially, in rural areas and for females. The biggest shortage is of science, mathematics and language teachers. There has never been any detailed planning on meeting teachers’ requirements both from a demand and a supply perspective despite the massive challenges. This lack of planning is one of the causes of teacher shortages. The other being even more damaging, politically driven deployments that fail to consider the needs of children in different areas. Many teachers, especially females, recruited against specific districts, get posted in larger cities through temporary arrangements that continue for years. There is a clear case of inefficient use of the available teacher resource.

Professional development of teachers was also identified as a weak area despite the recently initiated continuous professional program in limited districts. It is simply a supply-driven in-service teacher training approach. The Directorate of Education (Schools) that employs teachers does not recognise teacher professional development as its function and has left it entirely to the Provincial Institute of Teacher Education (PITE). This results in low priority accorded to Continuous Professional Development (CPD) in the Directorate and its field units. Areas like mentoring by headteachers, evaluations and peer learning are completely neglected as components of professional development. Even in case of the limited in-service teacher training capacity of Provincial Institute of Teacher Education (PITE) remains below par, and according to feedback received had very low impact. It requires major improvements.

Assessment and Examinations

III. Assessment and Examinations

Assessments and examinations both within school and large scale, taken by the Balochistan Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education (BBISE) are of a poor quality that only test for memory. They reinforce rote learning and discourage critical analytical thinking.

Capacity Limitations

IV. Capacity Limitations

Overall, there are serious capacity limitations of all organisations producing quality products like curriculum, textbooks and assessments and also the implementing body: the Directorate of Education (Schools). More critically, there is an absence of a structured standards regime. The nationally developed Minimum National Standards for Quality Education (MNSQE) are at a very high level and will need standards at the input and process levels for each of the areas (curriculum, textbooks, teachers, assessments etc.) to operationalise their implementation. Even intermediate standards may need to be developed before the requirements of MNSQE can be met.

Child Welfare

V. Child Welfare

Finally, the child. Welfare of the child has been the most neglected area for improvements in the teaching-learning processes in the classroom. Much is not known about child welfare as it is a poorly researched area. The most data is available on health of the pre-school children. It indicates a worrying situation: Balochistan has the lowest percentage of fully-immunised children, highest percentage of under-five children suffering from Diarrhoea and the lowest intake of micro-nutrient intake in Pakistan. About 47% of children under the age of 5 are stunted. There is no information available on psycho-social development of the child. A few interviews conducted with public health workers provided some anecdotal evidence on neglect and even corporal punishment. Much more research is needed.

However, the limited data available clearly indicates that the child enters school with multiple disadvantages. Minimisation of these disadvantages requires quality early childhood education. Presently less than 10% of early childhood education is based on the required curriculum and delivered as per the requirements of a quality Early Childhood Education (ECE). Most children attend the traditional kachi classes where children of these levels are ignored in multigrade situations (72% of all primary schools are multigrade with 43% being single teacher institutions).

Once in school, disadvantages continue. Children face situations of missing facilities that include lack of functional toilets and water availability. Corporal punishment, bullying and a school environment with low regard for safety are common. There are no health inspections or preparation of children for emergencies. Even where laws like Balochistan Child Protection Act 2016 exist to prevent all types of abuses against children, including inside school, nothing has been implemented, and vulnerability of the child continues. In terms of attitudes, there are no processes to develop inclusiveness in the schools. There are some additions on gender in the recently developed textbooks, but there has been no assessment of needs of inclusion in multi-lingual and multi-ethnic classrooms. Neither the physical nor social environments of schools accommodate inclusion. Children remain vulnerable in a hierarchical school environment within a system that does not place them at the center of policies, plans and service delivery.

Children with special needs fare even worse. They have very limited opportunities. The Directorate of Special Education runs only 11 institutions. These do not fully cover the needs. There is no coordination with the Directorate of Education (Schools) to develop a structured process for inclusion of children with special needs, to the extent possible, into regular schools. This remains a low priority area. Even data is inadequate.

Access and Participation

17.2.2. Access and Participation

The province has the highest percentage of out of school children, widest gender gaps and large areas without schools. The system of access, despite improvements in recent years, needs massive attention. A massive 65%96 children between the ages of 5 and 16 are out of school. This is the worst percentage out of all provinces. Survival rates to Primary level in Balochistan is 41 compared to 67 – which is the Pakistan average.

Female disadvantage is evident from the gaps in net enrolment rates over the years. Two trends are evident. Net enrolment rates decrease with levels of education, and they are lower for females at each level with the rural female being the worst off.

96 This is calculated by estimations based on the 2107 census, with an estimation that 40% are enrolled in private schools, along with a 12% (10% for boys and 2% for girls) enrolment in madrassas.

Table 17-2 Net Enrollment Rates 2014-15

|

Net Enrolment Rates 2014-15 |

|||

|

|

Primary 6-10 |

Middle

11-13 |

Secondary

14-15 |

|

Overall |

56 |

26 |

15 |

|

Overall Male |

67 |

31 |

19 |

|

Overall Female |

42 |

19 |

9 |

|

Rural Male |

63 |

29 |

15 |

|

Rural Female |

32 |

13 |

5 |

|

Urban Male |

78 |

36 |

26 |

|

Urban Female |

65 |

30 |

16 |

|

Source: Various PSLMs |

|||

Rural females have a net enrolment rate of 5 only at the secondary level. About one-third of the urban female which at 16 is also low. Gaps in Net Enrollment Rate (NER) are also reflected in enrolments in government schools. The number of girls enrolled is almost half that of the boys. A Gender Parity Index of about 0.51 for enrolment in government schools.

The situation of overall low participation and gender gaps has causes on both the supply and demand side. Demand-side factors, even as they are poorly researched, are used more conveniently for lower female participation. Data shows otherwise. There is a positive correlation between increase in schools for females and enrolment. A stark example is increase in female participation in examinations of Balochistan Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education (BBISE). Participation of females increased by 193% from 2001 to 2015. During the same period, female secondary schools increased from 100 to 250, an increase of 150%.

Low access and participation indicators owe to a number of factors. These include inadequate coverage of population by schools, poor learning in classrooms and limited availability of post-primary opportunities. Again school availability for females is lower at each level. Female primary schools are 27% of the total, middle 41% and secondary 33 %.

Overall also Balochistan has the most skewed school’s proportions. Primary schools constitute 80% of the all public-sector institutions in the province. Middle schools constitute 11% and secondary and higher secondary 8 and 1 percent, respectively.

Figure 17-3 Public Sector Institutions in Balochistan

On the demand side, poverty appears as the most important determinant for dropouts and overall out of school children. The high dropouts at primary level signify the increased opportunity cost for families as the older children support in income and non-income earning activities. With low expectations from education, families have few incentives to retain children in schools. There are other demand-side factors also. In case of females, early marriages also appear to play a role in discontinuation of education beyond certain grades. However, the demand-side considerations other than economic need to be researched better as knowledge is mostly speculative and limited.

In addition to generally low participation of the girl child, there are issues within school that have not been considered in her case. Many adolescent girls do not attend school due to lack of knowledge on menstrual health management. These specialised needs are missing in both society and schools.

A weak non-formal education system has not been helpful in reduction of out of school children and improvement of adult literacy. There are major gaps in governance as the singular Directorate with limited presence in the districts has struggled to expand NFE in the province or even manage the quality of the programs.

Research and Data

17.2.3. Research and Data

There has been progress on datasets design and expansion since the last Education Sector Plan. A more integrated, and expanded, EMIS now exists. It will roll out with time. However, there is still a need for a more comprehensive demand analysis of data and development of a culture of data use. There has been no assessment of data needs even for the fundamental documents like Balochistan Compulsory Education Act 2014 and Sustainable Development Goal 4. In case of the former, even indicators have not been developed while for SDG 4, no assessment has been made of the indicators to be used by Balochistan and the data needs thereof. Major gaps in data availability persist, including no information on private schools and madrassas. Meaningful reform, planning and monitoring of progress is not possible without generation and availability of data for the missing areas.

Research has remained as neglected, within the government, as it was five years ago. There has been no improvement in either the desire or the capacity to conduct research. Unless the situation is rectified, disconnect between needs of education on ground, and policy, plans, design and implementation will continue to widen. There has to be a recognition that a group of experts around a table cannot supplant the need for hardcore academic research triggered as per need on an ongoing basis. The research functions of all quality organisations continue to be dormant, and there has been no effort to connect to research work and capacity of the academia. Resultantly, policies and plans continue to be developed either without or with very little research.

Governance and Management

17.2.4. Governance and Management

Governance and management issues cut through all aspects of education service delivery. Under Governance and Management, the ESA focuses on the more overarching issues affecting the performance of the education system in Balochistan.

Increased spending on education has not translated into improved learning outcomes. The percentage of out-of-school children has not recorded any major reduction either. There are two major explanations for this. First, the overall education planning and resource allocation is not aligned with the goal of learning. Secondly, the education system has a weak ability to translate increased spending into better learning outcomes. This weak systemic ability, in turn, is explained by poor governance and weak management capacity of the education system in the province.

Governance and management issues cut through all aspects of education service delivery and are arguably the weakest link in Balochistan’s education system. Governance issues include standards, regulation, information, accountability, transparency and politics. Management covers policy and legal frameworks, structures, processes (planning, implementation and monitoring and evaluation), and capacities. The issues of lack of standards and weak capacity are of cross-cutting nature and have, therefore, been dealt with throughout BESP.

Poor governance framework and weak management capacity at all levels of education (including schools) is arguably the most serious problem of education service delivery in Balochistan. Key governance and management challenges include but are not limited to weak policy, regulatory and legal frameworks, ad hoc and centralised planning, inefficient HR management system, lack of clarity over mandates, unavailability and opacity of data on performance, low accountability, and lack of sustained political support. Most other problems in the education sector are somehow linked to poor governance and management. Prevalence of these issues means that the education system lacks the capacity to efficiently and effectively utilise available physical, human and financial resources. It also implies that increased availability of resources for education alone may not address the crisis of learning and low access.

The governance and management challenges explained above are compounded by the large, complex, and multi-layered organisational structure of the Secondary Education Department. With an employee strength of nearly 79,000 personnel spread horizontally and vertically across all tiers of governance (province, division, district and school), the SED is the largest department in the province in terms of human resource and infrastructure. SED’s 13,874 schools are spread across all tehsils and districts of the province. Nearly one million children attend these schools. The province is also home to a large number of Madrassahs and private schools. The latter have experienced mushroom growth over the last couple of decades. While the number of schools and students has increased, the fundamental management structures have remained, largely, unchanged even though there have been incremental changes.

Technical and Vocational Education and Training

17.2.5. Technical and Vocational Education and Training

The main problem in technical and vocational training and education is the failure to get most of its graduates absorbed into the market. It also results in low attraction of youth to participate in the sector. Absence of market research, weak governance capacity, lack of coordination with the market and non-utilisation of the capacity of the private sector are some of the key causes that impede development of the sector. Again options for females are limited. Only 35% of participants are women, mostly in low mobility trade.

No comments:

Post a Comment