Balochistan Education Sector Plan Context

Context

2.1. DEMOGRAPHY 2.2. ECONOMIC CONTEXT 2.3. SOCIAL CONTEXT 2.4. GENDER CONTEXT 2.5. SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OVERVIEW 2.6. VULNERABILITY TO NATURE 2.7. CONCLUSION

2. Context

Balochistan’s natural assets provide it with vast opportunities. Over the years, these assets have remained under-utilised due to a myriad of reasons but none more significant than poor human resource development. The province lags the rest of the country in all development indicators: population growth, poverty, health and education. Progress will require answers to the ecological challenge, especially water scarcity, and development of human resources to not only benefit from emerging opportunities but also to meet the challenges of social development and optimize the economic returns on its natural assets. This chapter outlines some of the contextual opportunities and risks that should be considered in all human resource development reforms. It covers the demography, economy, social structures, social development indicators, including the gender gap, and vulnerability of the province to nature.

Demography

2.1. Demography

Balochistan’s demography has three key dimensions: a low population density, a high population growth rate and a youth bulge. Each of these features has ramifications for development. Low population density means greater cost per unit; high population growth means increased challenges in each population cluster while the youth bulge creates opportunities and risks dependent on the response from the government. An additional dimension is the refugee population that has been a continuous factor since 1980.

Low Population Density

2.1.1. Low Population Density

Balochistan accounts for nearly 44% of Pakistan’s total land area but is home to only 6% of the country’s total population. The province has a population of 12.34 million, which is scattered over a large swath of arid, inhospitable and mountainous terrain (347,190 square kilometers). It has the lowest population density of all provinces (36 per sq. km. compared to the national average of 261 per sq. km.). A small population in a vast geographic region with a poor communication infrastructure means that the unit cost of public service delivery in Balochistan is significantly high compared to other provinces. This has implications for the development model and expenditure.

High Population Growth Rate

2.1.2. High Population Growth Rate

Balochistan has the highest population growth rate among the provinces of Pakistan. Its population increased from 6.56 million in 1998 to 12.34 million in 2017, registering an increase of 88%. The average annual growth rate was 3.37 percent during this period.4 Of the

12.34 inhabitants, over 72% live in rural areas. In what is a reflection of the broader national trend, the population of males (52.5%) in Balochistan is greater than that of females (47%.5).5 The total number of households is 1.78 million approximately.

The Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) 2017-18, reveals that Balochistan has one of the highest fertility rates in the country (See Figure 2-1) The Total Fertility Rate6 in Balochistan is four births per woman against the national average of 3.6 births per woman.

4 2017 Census Report Provisional, Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Government of Pakistan

5 Ibid.

6 The average number of children a woman would have by the end of her childbearing years if she bore children at the current age-specific fertility rates. Source: National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan] and ICF. 2019. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18. Islamabad, Pakistan, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NIPS and ICF

Figure 2-1 Total Fertility Rate by Region

Source: Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) 2017-18. National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS), Pakistan

High fertility rates predict a continued increase in population. The growth rate in population clusters places further stress on core public resources such as education and health and emphasizes the need to improve the productivity of its human resource on an emergency basis.

Youth Bulge

2.1.3. Youth Bulge

The province has a young population. Figure 2-2 illustrates the age and sex structure of the province’s population.7 The population pyramid has a broad base that narrows down as one moves up the pyramid. The degree of shrinking of the pyramid is particularly acute after the age of 29. The broad and relatively squarish base indicates a combination of falling child mortality rates and high birth rates.8 The narrow top of the pyramid shows short life expectancy and high death rates. Most of the population is clustered around the bottom of the pyramid. Nearly 65% of the population is below the age of 30, indicating that the province is experiencing a youth bulge. 9

7 The age break-down of the 2017 Census is not yet available publicly. These estimates are based on the population projections of the National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS).

8 For details, see: Sathar, Zeba, Rabbi Royan, and John Bongaarts (eds.). 2013. "Capturing the demographic dividend in Pakistan." Islamabad: Population Council.

9 National Insttute of Population Studies (NIPS) Population Projections for 2019

Figure 2-2 Balochistan Population Pyramid 2019

Source: National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) Population Projection 2019

Balochistan’s large youth bulge presents both an opportunity and a risk for its education system. On the one hand, it means that the education system can equip students with skills demanded by the market. On the other hand, youth bulge means that the education system will have to cope with the entry of a large number of children and young people into schools, colleges, universities, and programs for technical and vocational education and training. The education system will also have to review the types of skills that it teaches to students. If the education system fails to prepare young people for life and livelihood, then the youth bulge may become a demographic time bomb.10

Refugee Population

2.1.4. Refugee Population

According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), there are currently 324,280 registered Afghan refugees in the province.11 There is also an equally large number of those who are unregistered. The ethno-linguistic ties between refugees and certain ethnic groups of Balochistan, mainly Pashtuns and Hazaras, make Balochistan a prime destination

10 Pakistan National Human Development Report 2017 Unleashing the Potential of a Young Pakistan, United Nations Development Program Pakistan

11 UNHCR Website 2019

for Afghan refugees coming to Pakistan. Over the past decade, many refugees have returned to their country. However, a significant number still remains in the province. They have become a vital part of the socio-economic fabric of the region. Despite organised external support for refugees, their influx puts a strain on existing resources and services. This is primarily due to large refugee populations living outside designated camps.

Economic Context

2.2. Economic Context

The province has the lowest per capita income and the weakest growth performance over the past few decades compared to other provinces of Pakistan. Between 1972 and 2005, Balochistan’s GDP is estimated to have grown at an average rate of 4.1 percent per year in real terms.12 The region’s GDP has lagged that of other provinces by at least one percentage point annually since the early 1970s. Key barriers to growth include a poor security situation, low population density, a weak fiscal base, uncertain and limited supply of water, low investment, a weak private sector, and an inadequate institutional and human resource base.

Figure 2-3 GDP Growth by Region (1972-73 to 2004-05)

(PKR Millions, 1980-81 prices)

Source: World Bank, Balochistan: Development Prospects and Issues 2013

The province has a small industrial base, mostly located around Hub, near Karachi, and an underdeveloped services sector. The latter’s share has remained relatively stagnant in Balochistan, increasing from approximately 42% in 1972 to 47% in 2010. In contrast, the services sector has registered tremendous growth in other provinces, with its share in GDP rising to 55% or more in 2010.13

Even the existing assets perform way below their potential due to the reasons cited earlier.

12 The World Bank, Balochistan: Development Issues and Prospects (Multi-donor Trust Fund World Bank, Islamabad, 2013), p. 23

13 Ibid.

Key Economic Assets

2.2.1. Key Economic Assets Balochistan has many economic assets that, despite the high potential, continue to yield low dividends. The main assets are mines and minerals, location, livestock and agriculture and coastal area with potential for fisheries14.

Minerals

I. Minerals

Balochistan has large deposits of coal, copper, lead, gold, chromite and other minerals. Despite having an abundance of mineral resources, the mining sector in the province remains very small. This sector has tremendous potential to become a major contributor to the provincial GDP. However, weak governance, a dearth of geological data, poor connectivity, and lack of required skills and technology have impeded realization of the sector’s true potential.

Location

II. Location

The province’s landmass endows Pakistan with a vital strategic space for both security and regional trade. Balochistan connects South Asia with the strategically and economically important regions of Central Asia and the Middle East. This important strategic location, as well as, the large coastline make it a gateway and hub for regional transit trade.

The CPEC Opportunity

Box 2-1 The CPEC Opportunity

A significant opportunity is the multi-billion dollar China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) that has opened up new avenues for growth and development in the province. CPEC has the potential to create jobs, bridge major infrastructural gaps, address energy needs and foster industrial development in Balochistan. The realization of this potential can be made possible only through adopting an inclusive and participatory approach to development. The Federal and Provincial Governments need to undertake a whole lot of reforms and corrective measures to make the most of the opportunities arising out of CPEC. Human resource development should be central to these reforms, along with structural changes in the sectors discussed above.

Balochistan’s enormous locational and natural resource potential, however, remains

untapped. An opportunity is arising through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)

– See Box 2-1.

Agriculture & Livestock

III. Agriculture & Livestock

With over 30% share in the province’s GDP, agriculture has remained the most important sector of the economy. It employs over 40% of the total Labor force and provides livelihood to more than half of the province’s population. The share of agriculture in GDP has dropped from 35% in 2007 to 30% in 2016.15 Notwithstanding this decline, Balochistan’s economy still remains more dependent on agriculture than that of other provinces. Between 1972 and 2010, the share of agriculture in GDP decreased by 19, 11, and 22 percentage points respectively in the Punjab, Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa16. In contrast, the GDP share of agriculture in Balochistan fell by a mere 5 percentage points during the same period.17

Over the past decade, agriculture and livestock, transport and wholesale, and manufacturing respectively have remained the biggest sectors of the economy, accounting on average for 77%

14 Balochistan Economic Report 2009; World Bank

15 Government of Balochistan, Budget White Paper 2017-18

16 The World Bank, Balochistan: Development Issues and Prospects (Multi-donor Trust Fund World Bank, Islamabad, 2013), p. 23

17 Ibid

of the province’s GDP.18 The mining sector’s contribution to provincial GDP has averaged around 5% during the same period. A critical analysis of the structure of Balochistan’s economy reveals several significant trends and lessons for policy-making and growth planning.

Agriculture, which is the backbone of the province’s economy, is highly dependent on reliable availability of water. Balochistan currently faces severe water scarcity and is vulnerable to seasonal and permanent droughts. Between 1878 and 2013, it experienced 13 mild, 12 moderate, and 8 severe droughts with an average duration of 9, 11 and 13 years, respectively.19 The total annual water demand in the province is about 6.26 MAF. Agriculture constitutes nearly 80% of this demand and consumes about 70-80% of underground water and nearly all of the surface water20.

The province relies primarily on underground water and non-perennial surface water, except the Kachi plains that are connected to the Indus Basin Irrigation System through canals. More than two-thirds of the surface water remains unutilised, owing to the inadequate water harvesting capacity and limited storage infrastructure.21 Underground water is over-utilised, leading to depletion and exhaustion of this resource. Climate change has further increased variations in precipitation and vulnerability to droughts.

Given the lack of reliable water access, the excessive reliance on agriculture in the province for livelihood is unsustainable. This implies that a strategy to reduce dependence on agriculture and facilitate the transition to sustainable farming practices and techniques should be an integral part of future growth policy and plan for the province. In the absence of such a transition an ecological and economic disaster remains inevitable.

Coastal Area

IV. Coastal Area

The province possesses nearly 750 km long coastal belt—accounting for almost two-thirds of Pakistan’s total coastline. Due to this, the fisheries sector offers great potential for becoming agents of economic development in the province.

The coastal area also provides an opportunity to develop renewable energy using wind. This, again, remains an under-utilised potential. In the case of renewable energy, the possibilities and potential for solar are also high.The realization of this potential, however, is constrained by a combination of institutional and financial constraints.

Social Context

2.3. Social Context Balochistan’s social context is defined by three critical factors: ethno-linguistic diversity, tribal structures and limited urban dwellings.

Ethnicity and Languages

2.3.1. Ethnicity and Languages

Balochistan is one of the most diverse and linguistically-heterogeneous provinces22 of Pakistan. According to the 1998 census, 55% of the population identify themselves as ethnic-

18 Government of Balochistan, Budget White Paper 2017-18

19 Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: Balochistan Strategic Master Plan 2015-2025

20 Department of Irrigation, Feasibility Study for Development of Water Resources with the Construction of Small and Medium Dams in Balochistan (Government of Balochistan, Quetta, 2017)

21 Ibid.

22 The Balochistan Mother Languages as Compulsory Additional Subject at Primary Level Act, 2014 recognises Balochi, Pashto, Brahui, Sindhi, Persian, Punjab and Siraiki as mother languages of Balochistan.

Baloch23. This figure also includes the Brahui-speakers of the province as a part of the larger Baloch ethnic group (the other part of the group speaks Balochi).

Pashtuns are the second-largest ethnic group in the province, making up approximately 30% of the population. Sindhi-speakers are the third major linguistic group and account for almost 6% of the total population. Sindhi-speakers are followed by the Punjabis (3%) and Urdu- speakers (1%). The latter two often collectively referred to as the “settlers”. The Hazaras are another minority ethnic group. A people of Mongol descent, the Hazaras have a population of approximately 500,000 and speak Hazargi, which is a dialect of Persian. They are classified under “others” in the 1998 Census.

A salient aspect of ethnic diversity in Balochistan is the settlement pattern. The main ethnic groups in the province are regionally segregated. Most of the Pashtuns live in the districts north of Quetta, including Pishin, Killa Abdullah, Zhob, Loralai, Killa Saifullah etc. The Brahuis form a majority in districts of central Balochistan such as Mastung, Kalat and Surab. Balochi-speakers reside primarily in southern, western and pockets of eastern Balochistan. Sindhis are mainly concentrated in the Southeast and the Kachi plains.

Tribal Structures

2.3.2. Tribal Structures

Tribal networks and tribalism define the social mode of organisation among major ethnic groups in the province. The “tribe” can be broadly defined as a “kinship-based group with a shared history, exclusive customs and myths, and coherent internal systems of leadership and collective action”.24 With few exceptions, the Baloch, Brahuis and Pashtuns have a very comprehensive tribal system characterised by a clear leadership structure and lineage patterns, strong bonds of affiliation and well-defined dispute resolution mechanisms.25

Tribal networks and systems play a key role in political mobilisation and management of collective action. Tribalism and ethnic diversity have defined the politics of Balochistan in profound and diverse ways. It has encouraged the provision of public services through patronage networks and prevented the emergence of inclusive political parties and stable coalitions among ethnic elites.26

This complicates consensus on policy or development priorities.

Gender Context

2.4. Gender Context

Patriarchy is the building block of social organisation in Balochistan. Specific gender roles are defined vis-à-vis space, Labor, and authority. The role of women is limited mainly to the four walls of the house for an overwhelming majority. Gender segregation in public spaces is a key feature of public life. Women’s access to basic public services is limited compared to men. Political, economic and social authority is almost always reserved for men. Of all the provinces of Pakistan, Balochistan has the lowest percentage of women (10%) who participate in major household decisions, including decisions pertaining to health care, major household purchases, and visits to family or relatives.27 Similarly, Balochistan has the highest percentage of women who have experienced physical violence (49%) since age 15.28

23 The language-wise breakdown of the 2017 census is not available.

24 Haris Gazdar, Balochistan Economic Report: Background Paper on Social Structures and Migration (Karachi: Collective for Social Science Research, 2007), pp.14

25 Haris Gazdar, Balochistan Economic Report: Background Paper on Social Structures and Migration (Karachi: Collective for Social Science Research, 2007), pp.14-15

26 Rafiullah Kakar, ‘Understanding the Balochistan Conundrum’. In B Zahoor, R Rumi (eds.) Rethinking Pakistan (Lahore: Folio

Publishers, 2019)

27 Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18. National Institute of Population Studies, Pakistan

28 Ibid.

Figure 2-4 Spousal Physical, Sexual or Emotional Violence Experienced by Ever Married Women 15-49

Source: PDHS 2017-18. NIPS, Pakistan

With the advent of information technologies and the expansion of higher education, patriarchy is increasingly coming under pressure, especially in urban areas. An increasing number of girls are going to Universities and joining various professions.

Female participation in the Labor force is low at 9.7% as compared to 82.5% for males – overall Labor force participation rate for 15 plus being 49.4 %.

Figure 2-5 Labor Market Analyses for Balochistan 2017-18

Source: Employment Trends 2018 Pakistan’ Pakistan Bureau of Statistics

The situation for employment to population ratio is similar for 15 years and above. For youth (15 to 24 years) the ratio of female participation declines to 6.7% though at this age overall participation also reduces as part of the group is in schools.

Socio-Economic Development Overview

2.5. Socio-Economic Development Overview

Balochistan is the least-developed province of Pakistan, lagging in nearly every important indicator of social and human development. According to the United Nation’s Human Development Index 2015, it has the lowest HDI score of all the provinces in Pakistan and is the only one to fall in the low human development category. Balochistan’s score is 0.421 as against the national score of 0.681.29

Poverty

2.5.1. Poverty

According to the Multi-dimensional Poverty Index 2016 - which measures not only monetary deprivation but also standard of living and access to health and education services- Balochistan has the highest rate of multi-dimensional poverty among all provinces in Pakistan.30 Nearly three out of every four persons in the region are living in multi-dimensional poverty. Similarly, Balochistan also has the highest average intensity of deprivation (55%) among all provinces. This means that each poor person in the province, on average, is deprived in more than half of the indicators included in the index. It is worth noting that regional discrepancies of intensity of deprivation are not as stark as those of poverty headcount.

Figure 2-6 Pakistan Multi-dimensional Poverty Index 2016

Source: Pakistan Multi-dimensional Poverty Index 2016

29 Pakistan National Human Development Report 2017 Unleashing the Potential of a Young Pakistan, United Nations Development Program Pakistan

30 Pakistan Multi-dimensional Poverty Index 2016

Figure 2-7 Multi-dimensional Poverty Index Score by Region

Source: Pakistan Multi-dimensional Poverty Index 2016

Over the past two decades, Pakistan has experienced a significant reduction in poverty, with the total poverty headcount declining from 55% in 2004-05 to 39% in 2014-15. However, the pace of reduction was not uniform across provinces. Poverty reduction was lowest in Balochistan, where the headcount fell by 12.2 percentage points between 2004-05 and 2014-15. This is even more striking given that Balochistan had a high level of poverty in the baseline year for the study. In contrast, poverty headcount in the Punjab, Sindh and KP fell by 18.3, 14.2 and 16.6 percentage points respectively, during the same period. A similar study by the World Bank (WB) corroborates the finding that poverty reduction has been the lowest in the Balochistan province between 2001 and 2015.

Within Balochistan, there are variations among rural and urban areas and different districts. Multi-dimensional poverty in rural areas of the province (85%) is significantly higher than in urban areas (38%). Quetta, Kalat, Khuzdar, Gwadar and Mastung, in that order, are the least poor districts, whereas Chaghi, Ziarat, Barkhan, Harnai and Killa Abdullah respectively are the poorest districts in the province. The pace of progress has been uneven within Balochistan. While most districts in the province have reduced their poverty headcount between 2004 and 2015, few districts have recorded an increase in poverty incidence. The latter include districts of Harnai, Panjgur, Killa Abdullah, Ziarat and Pishin. The Districts of Musakhel, Khuzdar, Loralai, Turbat and Mastung respectively have registered the highest decrease in poverty in Balochistan during the same period.

Standard of Living and Basic Social Services

2.5.2. Health, Standard of Living and Basic Social Services

Again Balochistan fares worst of all provinces on nearly all indicators of health, education, standards of living and access to basic services. It has the lowest percentage of fully- immunised children, the highest percentage of under-five children suffering from Diarrhoea and the lowest rate of contraceptive use (16%) of all provinces. It has the highest Maternal Mortality Rate and the second highest rate of under-five mortality and stunting. Furthermore, people in Balochistan are the least-satisfied with basic public services such as health, education, family planning and agriculture.

Figure 2-8 shows the basic health indicators: fully immunised children, children under 5 suffering from diarrhoea, women that have received TT injections and doctor-assisted deliveries. Balochistan has the lowest figures in all except children suffering from diarrhoea.

Figure 2-8 Health Indicators

Source: Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (PSLM) Survey 2014-15, Pakistan Bureau of Statistics

Maternal mortality rates are given in Figure 2-9. They again show the highest number for Balochistan per 100,000 live births.

Figure 2-9 Maternal Mortality Rate by Region (Per 1,000 live births)

Source: UNICEF Report

Infant mortality rate in Balochistan is 78 per 1000 live births. This is lower than Punjab (85) but higher than all other provinces and areas. Another indicator that shows weak health services and practices.

Figure 2-10 Under-Five Mortality Rates by Region (Deaths per 1,000 live births)

Source: PDHS 2017-18. NIPS, Pakistan

Indicators on satisfaction with public services surveyed by PSLM 2014-15 again show Balochistan at the lowest level.

Stunting rates in under 5 is one of the most serious health issues.

“Substantive evidence indicates that low birth weight, reduced breastfeeding, stunting and iron and iodine deficiency are associated with long term deficits in children’s cognitive and motor development, and school readiness” EFA Global Monitoring Report 2007

Figure 2-11 Stunting rates in under 5

Source: PDHS 2017-18. NIPS, Pakistan

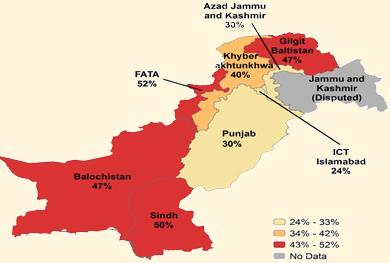

Balochistan has a stunting rate of 47% among children under 5 years. This is the second highest of all provinces in the country after Sindh. The other exception are the newly merged districts31 (NMDs) of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa where the rate is 52%. Stunting not only reduces physical growth, it also impacts brain development. This is a crisis.

Literacy Rates

2.5.3. Literacy Rates

Similar to other indicators, Balochistan has the lowest literacy rate in the country. This holds true for both the 10 plus and 15 plus categories. In the 10 plus, there is a slight improvement from 2010-11 to 2014-15, but still, the values are about 9 percentage points lower than the next lowest of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and 16 percentage points lower than the national literacy rate.

Figure 2-12 Provincial Comparisons of Literacy Rates for 10 plus

Source PSLM Survey 2014-15, Pakistan Bureau of Statistics

In the 15 plus category, the values go down for all jurisdictions, but the gap between Balochistan and others increases. Compared to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, it increases from 9 percentage points to 11 and from the national figure, the gap increases to 19 percentage points.

Figure 2-13 : Provincial Comparisons of Literacy Rates for 15 plus

Source Source PSLM Survey 2014-15, Pakistan Bureau of Statistics

Balochistan’s gender-wise breakup shows that female literacy rates are lower than males by a considerable percentage for all years and both categories – 10 plus and 15 plus.

31 These were previously the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA)

Figure 2-14 Comparison of Male and Female Literacy Rates in Balochistan

Source PSLM Survey 2014-15, Pakistan Bureau of Statistics

For the 15 plus category it is at 18 percent for both 2012-13 and 2014-15.

Vulnerability to Nature

2.6. Vulnerability to Nature

In the last three decades, Balochistan has seen three types of natural calamities: droughts, floods and earthquakes. Additionally, coastal areas have risks of cyclones. Recurring droughts are among the most significant challenges faced by the province, with serious implications for livelihoods. Only 5% of the region has a dependence on the Indus river – the primary water source for the other three provinces. There is a high dependence on groundwater and indigenous water channels. Excessive tube well installation in the 1980s for agriculture use has placed groundwater under threat. Resultantly every time there is a pause in rainfall for a longer period, droughts occur.

Additionally, the province has also seen increased flash floods when the rain pattern changes. There were major floods in 2010 and some in 2019. The last major earthquake was in Ziarat in 2008.

Conclusion

2.7. Conclusion

Balochistan faces an uphill development task. The challenges include threats to the environment and poor socio-economic indicators. It lags in almost all of the SDG indicators. However, there are also opportunities. These include, optimally benefiting from the province’s traditional assets and the new ones emerging out of the proposed China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Human resource development will remain central to the resolution of the developmental crises. This will require quality education for all children and the use of education to create awareness on the province’s developmental agenda.

No comments:

Post a Comment